Recently, the President signed into law two key pieces of legislation—the Cybercrime Prevention Act and the Data Privacy Act, both of which were meant to assist the development of the business process outsourcing industry in the country.

As late as last year, the Philippines reigned as the country with the biggest number of seats in the call center industry, as the BPO industry grew in terms of total revenue, foreign exchange inflow and employment generation.

Article continues after this advertisement

BPO lobby

FEATURED STORIESIt is believed that the BPO industry needs the Cybercrime Act (the “Act”) to respond to the demands of foreign clients for a strong legal environment that can secure their data from being stolen and sold.

As early as 2000, the E-Commerce Act (ECA) already punished hacking but the penalties were deemed too light. The persons convicted served no jail time if they opted to plead guilty in exchange for probation in lieu of imprisonment.

Article continues after this advertisement

Law enforcement agencies also faced various roadblocks when investigating cybercrime incidents. Even during emergency situations, service providers were reluctant to cooperate with law enforcement officers, citing the need to protect subscriber privacy.

Article continues after this advertisementTheoretically, search warrants would have addressed that problem but they were difficult to procure and involved a lengthy process that would have given cybercrime offenders enough time to delete precious data and cover their tracks.

Article continues after this advertisementIn cross-border cybercrime incidents, law enforcement efforts were even more challenging since foreign governments were not equipped to respond quickly to requests for assistance and no international framework was in place to address cross-border investigations and prosecution.

To be sure, no one in government was asleep at the wheel. The Philippine National Police (PNP) and the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), blessed with foreign-funded training in computer forensics and cybercrime investigation techniques, proceeded to organize and staff their cybercrime units. These were the two agencies that were very active in cybercrime investigation since the passage of the ECA.

Article continues after this advertisementBudapest Convention

Meanwhile, in the realm of international cooperation, the Department of Justice (DOJ) officially endorsed the Philippines’ accession to the Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime, also known as the Budapest Convention.

The treaty was fast becoming the vehicle to harmonize cybercrime definitions and promoted international cooperation in cybercrime enforcement and investigation. After all, the Budapest Convention was signed by many countries in Europe and even counted non-EU countries such as the United States, Canada, Japan, China and South Africa as among its member-states.

It was against this backdrop that various cybercrime bills were deliberated upon, in both houses of Congress. Earlier attempts to enact the law failed and it would take Congress more than 10 years to pass the Cybercrime Act.

Salient features

The salient features of the Act include internationally consistent definitions for certain cybercrimes, nuanced liability for perpetrators of cybercrimes, increased penalties, greater authority granted to law enforcement authorities, expansive jurisdictional authority to prosecute cybercrimes, provisions for international cybercrime coordination efforts and greater ability to combat cybercrimes.

Indeed, many of the cybercrimes defined under the Act hewed closely to the Budapest Convention and it borrowed heavily from the convention’s definition of illegal access and interception, data and system interference, misuse of devices, computer-related forgery and computer-related fraud.

Attempts now punishable

Under the ECA, cybercrimes can be prosecuted only if the offense was consummated. Unsuccessful intrusions or hacking incidents were not punishable. From a law enforcement standpoint, this means no arrest can occur until the harm or injury is actually inflicted upon the victims. Mere attempts were not punishable. Also, only the principal perpetrator was subject to criminal penalties.

These were addressed under the Act, where attempted cybercrimes are now punished and those who aid and abet the commission of cybercrimes are also made liable. This more nuanced approach to liability translates to greater flexibility in law enforcement and prosecution since cybercrimes can be stopped while being committed, though not yet consummated.

Stiffer penalties

The Act also increased the penalties from those imposed under the ECA. From the standard three-year prison term under the ECA, the Act increased the penalty to a period from six to 12 years for a lot of cybercimes. This ensured that any person convicted under the Act would surely face imprisonment since the option to apply for probation would no longer be available.

In direct response to the difficulties faced by law enforcement agencies in investigating cybercrime incidents, the Act gave greater authority to the PNP and NBI to engage in warrantless real-time collection of anonymized traffic data as well as the explicit authority to secure warrants for the interception of all types of electronic communication.

To prevent the destruction of precious evidence housed in various service providers like cell phone companies and broadband providers, the Act requires the preservation of data for a minimum of six months. This gives law enforcement authorities the ability to investigate past cybercrime incidents as well as lead time to get pertinent court orders to access such data.

The Act further specifies the means and manner by which law enforcement authorities should conduct computer-related searches and seizures of data, their custody, preservation and destruction.

Expanded jurisdiction

Since many cybercrimes are transnational in character, Congress vested in courts an expanded jurisdiction over the commission of cybercrimes. The pre-war Revised Penal Code took a more conservative stance and as a rule, the law was not applicable to acts committed outside the physical boundaries of the republic.

In contrast, the application of the Act was expanded beyond the Philippines so long as the perpetrator was a Filipino, or the effects of the cybercrime were felt within the country. In addition, the law applied if any of the elements were committed in the country or if these were done using equipment located here.

Cybercrime courts, office

Accordingly, to ensure the proper adjudication of cybercrimes, the Act mandates specialized training for judges in newly created cybercrime courts.

Since the Philippines has yet to enact the Budapest Convention and take advantage of the international cooperation available to its member-states, Congress, in the meantime, organized the Cybercrime Office at the DOJ and designated it as the central authority in all matters related to international mutual assistance and extradition. It is meant as a stop-gap measure, which hopefully can transition seamlessly when the country accedes to the treaty.

Emergency response team

Finally, the Cybercrime Act created the Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Center for policy coordination among concerned agencies and the formulation of a national cybersecurity plan that includes the creation of a computer emergency response team.

Clearly, the approach taken by Congress in the Cybercrime Act was to enlist the participation of various sectors of government to combat cybercrime not only at the national level but also internationally. While the BPO industry lobbied for the passage of the Act, it is undeniably a statute that applies to anyone who can potentially become a victim of cybercrime.

Unfortunately, not all statutes are perfect and although the best of intentions are embedded throughout the Act, some flaws in the law have caught the attention of the public, of late.

Petitions in high court

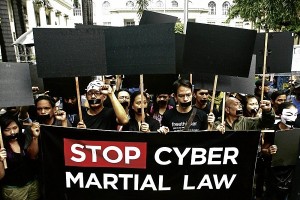

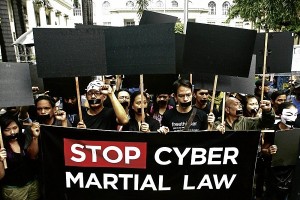

Indeed, various petitions have been lodged in the Supreme Court to question the constitutionality of the Act’s provisions relating to libel, increased penalties, real-time collection of traffic data and the so-called takedown provision.

Online libel was not an original creation under the Act. In fact, as early as 2010, the Supreme Court recognized that comments on a blog entry could give rise to a prosecution for libel. To its credit, the high court reasonably interpreted the law. The complainant argued that it was permissible to choose where to initiate the case upon the theory that online libel was published simultaneously throughout the Philippines.

Recognizing that the law did not allow a party to choose inconvenient venues for online libel cases, the Court limited the choice to only one—the place where the complainant resides.

One degree higher

The Act’s libel provision seemed harmless on its face. The law itself imposed no specific penalty unlike in other cybercrimes mentioned in the statute. But the Act provides that online libel is punished by one degree higher and that the prosecution under the law would still be independent of a separate prosecution for libel under the Revised Penal Code.

Under the old regime, an accused facing libel can expect to face no more than four years and two months jail time. Under the Act, the maximum penalty shot up to 10 years. Since the penalties were cumulative, a single act of online libel can attract a maximum jail time of more than 14 years.

Double convictions

The double convictions and the increased penalties made the accused ineligible for probation, thus guaranteeing imprisonment.

Since the acts and the crime of online libel are the same as that defined in the Revised Penal Code, it has been argued that the law violates the rule against double jeopardy which seeks to protect citizens against being penalized twice for the same offense.

Also, by imposing increased penalties for ordinary crimes committed “by, through, or with the use” of information and communications technologies (ICTs), Congress was unfairly segregating users of ICTs and treating them more harshly.

Protection clause violated

There seems to be no rational basis for this classification and the discrimination imposed by Congress violates the equal protection clause that requires the government to treat all citizens equally.

Since the online libel law targets the fundamental right to free speech, the onus is upon the government to demonstrate a compelling state interest in penalizing online libel in this manner, and show that there was no less restrictive alternative available to promote that interest.

In the desire to empower law enforcement agencies, the Act authorizes the PNP and the NBI to conduct real-time collection of traffic data, or data about a communication’s origin, destination, route, date, size and duration, but excluding identities and content.

In the context of mobile communications, traffic data will reveal the originating number, the destination number, the time and date of the communication, as well as the length of the conversation or the size of the SMS message sent.

Surveillance

The law enforcement authorities may claim that the traffic data are anonymous, but the fact is that the law allows collection of “specified communications,” which necessarily means the PNP or NBI must already know something about the communications or the identity of their source.

Even if they did not, it is easy to know the identity of a cell phone’s owner by simply dialing the number and employing various social engineering techniques to get that information. Once the identity of the person has been determined, the real-time collection of traffic data effectively becomes a targeted surveillance.

That is not to say that government authorities are prevented from engaging in surveillance, but the Constitution requires the intervention of a judge and the issuance of a warrant before this authority can be exercised.

Sadly, the real-time collection of traffic data under the Act does not afford anyone the same protection. Indeed, the privacy of suspected terrorists are protected to a greater degree under the Human Security Act that at least requires the intervention of the Court of Appeals in any surveillance and the careful handling of the evidence collected.

No similar protections exist under the Act, not even in the case of ordinary citizens. Certainly, these violate the right to the privacy of communications, and the right against unreasonable searches and seizure.

Most odious provision

Finally, the most odious provision of the Act is the so-called takedown provision that authorizes the DOJ to block access to any content upon a prima facie (or first glance) finding of a violation of the provisions of the Act.

This means that a person who believes he has become the victim of an online libel can file a complaint in the DOJ and if at first blush it appears there has been a violation of the Act, an order will be issued directing Internet service providers to block the content.

Under this scenario, the DOJ has effectively become the judge, jury and executioner without the benefit of a trial or a conviction established beyond reasonable doubt.

No time limit

The takedown order has no time limit and can be in place for years or even forever. The complainant is not required to file a case in court while the takedown order is in place. In fact, it is likely that no such case will ever be filed since the remedy sought has already been obtained, as the online content is already gone.

The takedown power can even be invoked to block sites wholesale such as those that allegedly violate the Retail Trade Law (Amazon, Alibaba, Ebay, iTunes) or offer voice services without the benefit of a local franchise (Skype, Googletalk) or facilitate copyright infringement (Piratebay, Filestube, Bittorrent) or allow online gambling (Pokerstars) or violate the Data Privacy Act (Facebook, Friendster).

These cumulative blocks and filters permit the DOJ to establish the Philippine equivalent of the Great Firewall of China. Certainly, with this takedown provision, the DOJ will be the most powerful authority on all matters involving the Philippine online community.

Prior restraint

From a free speech standpoint, the takedown provision is an effective prior restraint to the right of a person to express himself.

Even though the blocking of the content happens after the speech is made, the censorship that is done immediately or shortly after the posting of the allegedly offensive content, without the benefit of a trial or proof beyond reasonable doubt, is no different from preventing the speech itself.

Under constitutional law a prior restraint upon the freedom of expression is not permitted and is presumed to be unconstitutional.

The burden rests with the state to show that the suppression of speech is necessary to avoid a clear and present danger of evils, which such speech will bring about and which the State has a right to prevent.

In the case of the takedown provision, the grant of overbroad authority to the DOJ under all circumstances makes it difficult to hurdle the challenges against its constitutional infirmity.

Your subscription could not be saved. Please try again.